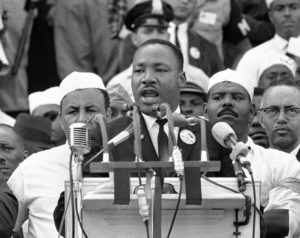

King’s most famous quote, in his most famous speech, was an audacious, in-your-face challenge to white people.

“I have a dream,” he said, “that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

The message is uplifting, yes, and is also laced with righteous anger, bitterness, and sarcasm. “I have dream,” indeed.

The reaction to that message still reverberates. Today, after a half-century of advances and setbacks, King’s challenge to white people is as stark as in 1963.

At the August 28, 1963 March on Washington

The 2016 presidential campaign was all about character. About being consistently poised and respectful, despite differences. About answering difficult questions directly and honestly. About doing your homework and knowing what you’re talking about. About listening and remaining persuadable in the heat of argument. About being protective of those who need protection. About speaking one’s mind, and standing up for what is right.

Those elements of character were the core appeal of the Democratic candidate—much more than mere ideology.

And it was a turn-off for many voters. For many white voters, that is.

Here’s what I’ve learned from being white: The existence of white supremacy, with the very real advantages if confers in status and opportunity—constitutes a moral hazard. Because it is all too easy to substitute white privilege for the very difficult effort of cultivating good character.

And the less one has accomplished through real effort and real accomplishment, rather than skating by on white skin, the greater the hazard.

The moral hazard of white supremacy can lead people to stay in economically hopeless backwaters rather than face the rigors of urban life. To stick with fading livelihoods rather than learning something new. To substitute the falsity of homilies and heritage for authentic development of one’s individuality. Enough years of this avoidance will, almost inevitably, cause a whole community to suffer hopelessness, which can be measured in rising substance abuse and mortality.

Many will also suffer anger, and resentment, against “elites” who live in a multiracial, diverse, challenging, and forward-looking world. And they may feel they are being judged and excluded for lacking the elements of character that are, more and more, indispensable currency in that world—urbane poise, open-mindedness, sensitivity to others, attentiveness to knowledge. (These elements of character are often derided as “political correctness.”)

Part of Trump’s appeal is that he offers a comforting reassurance to white people that, in America today, those “elite” character values can still be sidestepped. All you need is white skin and money, and you can be coarse, ignorant, racist, and successful. Without the money, you’re still OK.

So, Dr. King’s dream that his children (and ours) should be judged by the content of their character—that is still a dream. As we continue to pursue it, we would do well to remember that it is not just a “dream” in the sense of a high-minded aspiration, but a dream full of righteous anger at white supremacy.